Our current healthcare system causes harm. Healthcare providers take an oath to “do no harm” and their licenses dictate that they practice in an evidence based way. However, when the recommendation or prescription is weight loss, the healthcare provider is falling short of these 2 important tenets of providing care.

I dream of a day when our children’s healthcare is not weight-focused and rooted in weight bias and diet culture.

I dream of a day a teenager going through puberty doesn’t receive comments about their very normal weight changes.

I dream of a second grader being taught to trust themselves and their appetite rather than to fear food.

I dream of an expectant mother being nurtured and supported, rather than told she needs to “watch her weight.”

I dream of a day that a person in a larger body receives the same quality of care as a person in a smaller body.

I dream that one day our entire healthcare system will focus on the real determinants of health – genetics, socioeconomic status, trauma history, behaviors, support, stress levels, access to care – rather than weight.

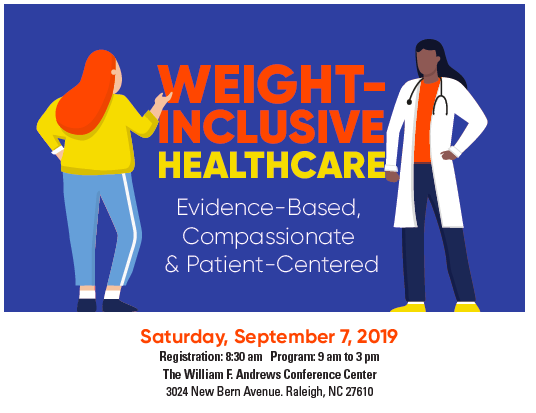

In September, I gave an one day conference titled “Weight Inclusive Healthcare: Evidence Based, Compassionate, Patient Centered,” with Louise Metz, MD of Mosaic Comprehensive Care and Rachel Porter, PsyD. Our goal was to bring the research and evidence of weight inclusive care, as well as the practice and “how-to’s,” to medical providers.

We applied for and received a grant from ASDAH – the Association of Size Diversity and Health. ASDAH is a not for profit organization for professionals committed to practicing using the Health At Every Size® principles. Their grant helped make the dream of a workshop on Weight Inclusive Care for physicians a reality.

We also teamed up with Wake AHEC (Area Health Education Center) which provides professional continuing education to healthcare providers in Wake County, North Carolina. Our Conference included the The Why, The What, and The How of Weight Inclusive Healthcare.

The Why:

The evidence is clear that weight focused health care is not evidence based. The weight and health research doesn’t support the commonly held idea that if people lose weight, they will be healthier. The BMI cutoffs that are used in healthcare are arbitrary and influenced by our diet industry.

Research shows that being in the “healthy weight” category does not reduce all cause mortality and actually individuals in the “overweight” BMI category have the lowest mortality rate (1). Weight loss research shows that most individuals that lose weight have gained the weight back at 5 year follow-up and ⅔ of those people gain back more weight (2-6).

This idea that if people just lost weight then they would be healthier is an “untested hypothesis,” as there is not a group of people to study that have sustained weight loss (7).

Weight and health research does show a correlation between weight and certain health markers (blood glucose, blood lipid levels, blood pressure). However, anyone who has taken a statistics class knows that correlation doesn’t equal causation.

For example, when you control for weight cycling in the very large Framingham and NHANES studies, the correlation between weight and health disappears (7). By prescribing weight loss, we’re feeding into weight cycling and thus causing harm.

A focus on weight loss in healthcare also creates and perpetuates weight stigma. The research is clear the weight stigma leads to poorer healthcare, avoidance of medical care, poorer health and mental health, and, yes, weight gain. Healthcare has been shown to have significant weight stigma and weight bias, compared to other professions (8, 9, 10).

The What:

Research shows that when we focus on behaviors, not weight, health parameters improve (11, 12, 13, 14) We presented a case study and illustrated the roles of the physician, psychologist and Registered Dietitian in the care of an individual. When we stop focusing on weight, we can begin to focus on true health determinants and behaviors that are relevant, attainable, and health enhancing.

The How:

From the moment a patient enters a medical facility there is the potential for harm to be caused.

Imagine: An individual walks into the waiting room of a doctor’s office and there is not a chair that is appropriate for their body. They are then brought back to the exam rooms and the medical assistant weighs the individual in a public place.

The patient then overhears medical staff talking about their latest diet and being “bad” for not sticking to it today. The patient enters the exam room for more vitals to be taken. The blood pressure cuff is too small, and thus, the reading is not accurate.

The provider then enters the room. The patient is at the medical visit for an ear infection and the doctor’s advice is to lose weight. At check out, the patient is handed a print out that includes the words “Obese” on it and a prescription for weight loss. At each step of the visit harm is caused.

We had nearly 80 healthcare providers in the room, including physicians, PA’s, Nurse Practitioners, Dietitians, Therapists, Nurses, and Intake Coordinators. Many of these individuals work at large institutions and others at smaller private practices.

We discussed steps towards creating a weight inclusive practice. This includes the physical equipment at a practice, policies around weighing patients, as well as the training of all staff.

Not all medical providers have input into all of these details at the pratice, but each provider can consider what is within their influence to practice in an evidence based way that reduces harm and supports true health.

We plan for this conference to be the beginning of many Weight Inclusive Conferences for medical providers. For the sake of our health and the health of the next generation, it’s time for a paradigm shift.

References:

- Flegal et al. 2005. JAMA. 293, 1861-1867.

- Stunkard AJ Arch Int Med (1959) 103: 79 – 85.

- Kassirer J N Engl J Med (1998) 338: 52 – 54.

- Anderson JW Am J Clin Nutr (2001) 74: 579 – 584.

- Wing RR Am J Clin Nutr (2005) 82: 222S – 225S.

- Franz MJ J Am Diet Assoc (2007) 107: 1755 – 176

- Campos P et al. Int J Epidemiol. 2006 Feb;35(1):55-60.

- Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity 2009. 17: 941–964.

- Hebl, Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001 Aug;25(8):1246-52.2001

- Friedman KE, Ashmore JA, Applegate KL, Obesity.2008; 16 (suppl 2):S69-S74

- Bacon et al J Amer Diet Assoc 2005, 105:929-936.

- Mensinger et al. 2016 Oct 1; 105:364-74.

- Tylka et al. J Couns Psychol. Jan;60(1):137-53.

- Khasteganan et al. Syst Rev 2019 Aug 10;8(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s13643-019-1083-8.